If you’ve been following along with my posts over the past six months or so you can probably imagine that I’ve been asked some variation of this post’s title more than a few times. One question that I keep getting is why I chose F# over some other functional languages like Haskell, Erlang, or Scala. The problem with that question though is that it’s predicated on the assumption that I actually set out to learn a functional language. The truth is that moving to F# was more of a long but natural progression from C# rather than a conscious decision.

The story begins about two and a half years ago. I had pretty much burned out and was deep into what I can only begin to describe as a stagnation coma. I stopped attending user group meetings; I cut way back on reading; I pretty much stopped doing anything that would help me remain even remotely aware of what was going on in the industry.

It’s easy to explain how I got to this point. My employer at the time gave very little incentive to stay current. For instance, there were homegrown frameworks for nearly every aspect of the product. Who needs NHibernate (or other ORM) when you have a proprietary DAL? Why learn ASP.NET MVC when you have a proprietary system for page layout? What’s the point of diving into WPF when the entire application is Web-based? Introducing new technologies or practices was generally discouraged under the banner of being too risky.

It wasn’t until the company hired a new architect that I started to wake up. He brought a wealth of knowledge of fascinating technologies that I’d hardly heard of and his excitement reminded me of what I loved about technology. My passion for software development was reigniting and I started looking at many of the technologies that had passed me by.

The first technology that really caught my attention during this time was LINQ. I’d consider it my introduction to the wonderful world of functional programming. As cool as I thought its query syntax was, I was really interested in the method syntax. I remember reading early on (although I don’t remember where) that query syntax was only added to C# after users complained that method syntax was too cumbersome in the preview versions. I didn’t understand this sentiment at all because to me method syntax felt completely natural. Gradually I began to realize that the reason it felt so natural was because it works the way I think. Lambda expressions, higher-order functions, composability, all of these functional concepts just spoke to me.

Over time I started using more of C#’s functional aspects but found myself getting increasingly frustrated. For the longest time though I couldn’t quite pinpoint anything specific but something just didn’t feel right anymore. It wasn’t until I was mowing the lawn late on a summer afternoon when I had that “a ha!” moment that changed my life.

That afternoon my yard work podcast selection included Hanselminutes #311. In this episode Richard Minerich and Phillip Trelford were talking about a functional language called F# that had been around for a few years and was built upon the .NET framework. I’d seen a few mentions of F# here and there but before hearing this podcast I hadn’t given it much thought.

At one point the discussion turned to language productivity and Phillip remarked that writing C# feels like completing government forms in triplicate. As he elaborated I experienced a sudden burst of clarity into one of the major things that had been bothering me about C# – it’s verbosity! After listening to the rest of the podcast and hearing more about how the functional nature of the language made it less error prone and how things like default immutability helped alleviate some of the complexity of parallel programming I knew I had to give it a try.

A language that doesn’t affect the way you think about programming, is not worth knowing.

— Alan Perlis, Epigrams on Programming

Despite my love of F# most of my work is still in C# but learning F# has had an amazing impact on how I write C#. C# has been becoming more of a functional language with virtually every new release and I’ve been using many of those capabilities for a few years but the language is hardly built around them. That said, forgetting about all the times I’ve typed let instead of var or tried to define a default constructor in the class signature in the last week alone F# really has changed the way I work. I find myself writing more higher-order functions and making much better use of delegation; I’ve developed a strong preference for readonly member fields and properties; and I regularly find myself longing for some of F#’s constructs like tuples, records, discriminated unions, and pattern matching.

The truth is that for all of its strengths though I’m finding working in C# increasingly annoying especially as I continue to work with F#. In many ways, working with C# feels like interacting with a toddler. I feel like I have to hold its hand and guide it along with explicit instructions on what to do every step of the way – even if I’ve already told it something. On the other hand, F# feels like having a personal assistant. Its functional nature allows me to more or less describe what I want and it handles the details.

There are plenty of things that make me prefer F# over C# but I’d like to highlight a few in particular. I’ve already written extensively about some of these and will be writing more about others as time permits but here I’d like to look at them from a more comparative angle.

Terse Syntax

Even though F# is a functional-first language I think a great way to illustrate the language’s expressiveness is with an object-oriented. We’ll start with a simple class definition in C#.

public class CircleMeasurements

{

private double _diameter;

private double _area;

private double _circumference;

public CircleMeasurements(double diameter, double area, double circumference)

{

_diameter = diameter;

_area = area;

_circumference = circumference;

}

public double Diameter { get { return _diameter; } }

public double Area { get { return _area; } }

public double Circumference { get { return _circumference; } }

}

// Usage

var measurements = new CircleMeasurements(5.0, 19.63495408, 15.70796327);

Look how much code was required to create a class with three properties. Even in this small example we had to tell the compiler what type to use for each value three times! I could have used auto-implemented properties to simplify it a bit but even then we still need to tell the compiler which type to use twice for each value. Now let’s take a look at the same class in F#:

type CircleMeasurements(diameter, area, circumference) =

member x.Diameter = diameter

member x.Area = area

member x.Circumference = circumference

// Usage

let measurements = CircleMeasurements(5.0, 19.63495408, 15.70796327);

That’s it – four lines of code. Granted this compiles to something that resembles the C# class but we didn’t have to write any of it and thanks to the fantastic type inference system we didn’t have to tell the compiler multiple times which type to use for each value. Quite often though even this is more verbose than we actually need. Many times we can use another F# construct – a record type – to represent something we’d represent with a class in other .NET languages:

type CircleMeasurements = { Diameter : float; Area : float; Circumference : float }

// Usage

let measurements = { Diameter = 5.0; Area = 19.63495408; Circumference = 15.70796327 }

In addition to being even more concise than the corresponding class definition, record types have the added benefit of being structurally comparable so we can easily check for equality between two instances. Record types do require us to include the type annotations but we only need to explicitly tell the compiler what to use once for each value and the constructor and properties are each created implicitly.

Functional Style

I already mentioned that functional programming feels more natural to me and by design F# really shines when it comes to expressing and using functions. Traditional .NET development has always had some type of support for delegation and it has definitely improved over the years, particularly with the common generic delegate classes (e.g.: Func, Action) and lambda expressions but actually trying to use them in a more functional style is a pain. This is complicated by the fact that in some situations the C# compiler can’t infer whether a lambda expression is a delegate or an expression tree. Although in some regards I prefer the C# lambda expression syntax I definitely prefer F#’s syntactic distinction between delegates and code quotations.

While on the topic of functional programming I have to mention F#’s default immutability. Immutability is key to any functional language and has been shown to improve overall program correctness by eliminating side effects. C# has some support for immutability through readonly fields or by omitting setters from property definitions but either of these require a conscious decision to enable. Nearly everything in F# is immutable unless explicitly declared otherwise. Immutability also provides benefits when writing asynchronous code because if nothing is changing, there’s a reduced need for locking.

Discriminated Unions

If you haven’t read my post on discriminated unions yet, they’re a way to express simple object hierarchies (or even tree structures) in a concise manner. From a syntactic perspective they’re incredibly simple but trying to replicate them even for simple structures really isn’t particularly feasible in C#. Here’s a simple example:

In this example suit is another discriminated union.

type Card =

| Ace of Suit

| King of Suit

| Queen of Suit

| Jack of Suit

| ValueCard of Suit * int

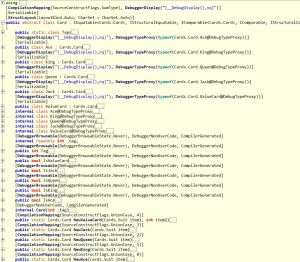

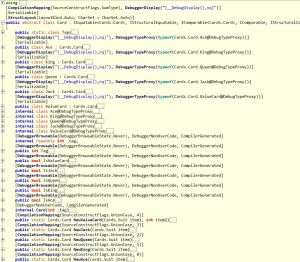

Using this discriminated union we express the 7 of hearts as ValueCard(Heart, 7). For illustration of what it would take to represent this structure in C# I’m including a screenshot of ILSpy’s decompilation. Note that I’ve only included the signatures and even this five case discriminated union more than fills my screen. Just to drive the point home, fully expanded, this code is nearly 700 lines long! Granted there are a few CompilerGeneratedAttributes in there but they hardly count for a majority of the code.

Ultimately, the union type is an abstract class and each case is a nested class. The nested classes are each assigned a unique tag that’s used for type checking and code branching in some of the union type’s methods. Not included in the screenshot are implementations of several interfaces and overrides of Equals and GetHashCode.

Decompiled Card Discriminated Union

Collection Types & Comprehensions

C# has made great strides in regard to initializing various collection types but it still pales in comparison to the constructs offered by F#. Don’t get me wrong, collection initializers are a nice syntactic convenience but nearly every time I use it I think how much easier it would likely be with a comprehension. LINQ can address some of these shortcomings but even convenience methods like Enumerable.Range feel limiting. Yes, I could write some additional convenience methods to address some of the shortcomings but in F# I don’t have to.

Part of the beauty of comprehensions is that they generally apply regardless of which collection type you’re creating. Although each of the examples below create F# lists they can easily be modified to create sequences or arrays instead.

// Numbers 0 - 10

> [0..10];;

val it : int list = [0; 1; 2; 3; 4; 5; 6; 7; 8; 9; 10]

// Numbers 0 - 10 by 2

> [0..2..10];;

val it : int list = [0; 2; 4; 6; 8; 10]

// Charcters 'a' - 'z'

> ['a'..'z'];;

val it : char list =

['a'; 'b'; 'c'; 'd'; 'e'; 'f'; 'g'; 'h'; 'i'; 'j'; 'k'; 'l'; 'm'; 'n'; 'o';

'p'; 'q'; 'r'; 's'; 't'; 'u'; 'v'; 'w'; 'x'; 'y'; 'z']

// Unshuffled deck

> let deck =

[ for suit in [ Heart; Diamond; Spade; Club ] do

yield Ace(suit)

yield King(suit)

yield Queen(suit)

yield Jack(suit)

for v in 2 .. 10 do

yield ValueCard(suit, v)

];;

val deck : Card list =

[Ace Heart; King Heart; Queen Heart; Jack Heart; ValueCard (Heart,2);

ValueCard (Heart,3); ValueCard (Heart,4); ValueCard (Heart,5);

ValueCard (Heart,6); ValueCard (Heart,7); ValueCard (Heart,8);

ValueCard (Heart,9); ValueCard (Heart,10); Ace Diamond; King Diamond;

Queen Diamond; Jack Diamond; ValueCard (Diamond,2); ValueCard (Diamond,3);

ValueCard (Diamond,4); ValueCard (Diamond,5); ValueCard (Diamond,6);

ValueCard (Diamond,7); ValueCard (Diamond,8); ValueCard (Diamond,9);

ValueCard (Diamond,10); Ace Spade; King Spade; Queen Spade; Jack Spade;

ValueCard (Spade,2); ValueCard (Spade,3); ValueCard (Spade,4);

ValueCard (Spade,5); ValueCard (Spade,6); ValueCard (Spade,7);

ValueCard (Spade,8); ValueCard (Spade,9); ValueCard (Spade,10); Ace Club;

King Club; Queen Club; Jack Club; ValueCard (Club,2); ValueCard (Club,3);

ValueCard (Club,4); ValueCard (Club,5); ValueCard (Club,6);

ValueCard (Club,7); ValueCard (Club,8); ValueCard (Club,9);

ValueCard (Club,10)]

Pattern Matching

faced with a 20th century computer

Scotty: Computer! Computer?

He’s handed a mouse, and he speaks into it

Scotty: Hello, computer.

Dr. Nichols: Just use the keyboard.

Scotty: Keyboard. How quaint.

— Star Trek IV

The above conversation enters my mind when I’m working with C#’s branching constructs, switch statements in particular. F#’s pattern matching may bear a slight resemblance to C# switch statements but they’re so much more powerful. switch statements limit us to simply branching on constant values but pattern matching allows value extraction, multiple cases, and refinement constraints for more precise control with a syntax much friendlier than your common if/else statement. Furthermore, like virtually everything else in F#, pattern matches are expressions so they return a value making them ideal candidates for inline conditional bindings.

Units of Measure

Every programmer works with code that uses different units of measure. In most languages dealing with units of measure is error prone because they require discipline from the developer to ensure that the correct units are always used. There are some libraries that attempt to address the problem but to my knowledge (please correct me if I’m wrong) F# is the only one to actually include it in the type system. F#’s unit of measure support is complete enough that it can often automatically convert values between units, particularly when a conversion expression is included with the type definition.

[<Measure>] type px

[<Measure>] type inch

[<Measure>] type dot = 1 px

[<Measure>] type dpi = dot / inch

let convertToPixels (inches : float<inch>) (resolution : float<dpi>) : float<px> =

inches * resolution

let convertToInches (pixels : float<px>) (resolution : float<dpi>) : float<inch> =

pixels / resolution

The biggest downfall of F#’s units of measure is that they’re a feature of the type system and compiler rather than a CLR feature. As such, the compiled code doesn’t have any unit information and we can’t enforce the units in cross-language scenarios.

Object Expressions

I haven’t written about object expressions yet but they’re definitely on my backlog. Object expressions provide a way to create ad-hoc (anonymous) types based on one or more interfaces or a base class. They’re useful in a variety of scenarios like creating one-off formatters or comparers and I think they can at least supplement, if not replace some mocking libraries. To illustrate we’ll use a somewhat contrived example of a logging service.

type LogMessageType =

| DebugMessage of string

| InfoMessage of string

| ErrorMessage of string

type ILogProvider =

abstract member Log : LogMessageType -> unit

type LogService(provider : ILogProvider) =

let log = provider.Log

member this.LogDebug msg = DebugMessage(msg) |> log

member this.LogInfo msg = InfoMessage(msg) |> log

member this.LogError msg = ErrorMessage(msg) |> log

Here we use a discriminated union to define the message types the logging provider interface can handle. The log service itself provides a slightly friendlier API than the provider interface itself. Normally if we wanted to use the log service instance we’d have to define a concrete implementation of ILogProvider but object expressions allow us to easily define one inline.

let logger =

LogService(

{ new ILogProvider with

member this.Log msg =

match msg with

| DebugMessage(m) -> printfn "DEBUG: %s" m

| InfoMessage(m) -> printfn "INFO: %s" m

| ErrorMessage(m) -> printfn "ERROR: %s" m

}

)

In our object expression we use pattern matching to detect the message type, extract the associated string, and write an appropriate message to the console.

> logger.LogDebug "message"

logger.LogInfo "message"

logger.LogError "message";;

DEBUG: message

INFO: message

ERROR: message

What’s Not So Great?

I could continue on for a while with things I like about F# but this post is already long enough as it is. That said, I think it’s only fair to list out a few of the things I don’t like about the language.

Tooling Support

Probably the biggest gripe I have is the lack of tooling support around the language. So many tools and templates that I take for granted when working with C# simply aren’t available. Things like IntelliSense are pretty complete but if you’re just getting started with F# and looking to do more than a console application or library be prepared to spend some time looking for 3rd party templates and reading blog posts.

Language Interop

On a somewhat related note, even though F# compiles to MSIL and can reference or be referenced by other .NET assemblies there are some quirks that make language interoperability a but cumbersome. For instance, using extension methods defined in C# doesn’t work as cleanly as I thought they would. When I was experimenting with MassTransit I couldn’t get the UseMsmq, VerifyMsmqConfiguration, or a number of other extension methods to appear no matter what I tried. I ultimately had to call the static methods directly.

I’ve read that this is addressed in F# 3.0 but I haven’t done enough with 3.0 yet to confirm.

Project Structure

It’s not really fair to put this under the “what’s not so great?” heading but it seemed most appropriate. This isn’t so much an issue with the language as much as it’s a big mindset shift of a similar magnitude of switching from OO to functional. The structure of an F# project is significantly different than that of a C# (or even VB) project and is something I’m still struggling with.

In C# we generally organize code into folders representing namespaces and keep one type (class) per file. F# evaluates code from top down throughout the project so file sequence is significant. Furthermore, code is organized by modules rather than type. F# does have namespaces but even then they’re usually divided across one or more files and from my experience, not grouped by folder.

Wrap Up

No matter what language you work in, programming in a functional style provides benefits. You should do it whenever it is convenient, and you should think hard about the decision when it isn’t convenient.

— John Carmack, Functional Programming in C++

In general I’ve found that the more I learn and work with F# the more I like it. I regularly find myself reaching for it as my first choice, especially when it comes to new development. Although there are a few things that I don’t like about working in F# most of them just require more diligence on my part or are easily managed. I’ve only listed a few key areas where I think F# excels but I firmly believe that their strengths far outweigh any weaknesses.