This is the fourth part of a series intended as an introduction to LINQ. The series should provide a good enough foundation to allow the uninitiated to begin using LINQ in a productive manner. In this post we’ll look at the performance implications of LINQ along with some optimization techniques.

LINQed Up Part 3 showed how to compose LINQ statements to accomplish a number of common tasks such as data transformation, joining sequences, filtering, sorting, and grouping. LINQ can greatly simplify code and improve readability but the convenience does come at a price.

LINQ’s Ugly Secret

In general, evaluating LINQ statements takes longer than evaluating a functionally equivalent block of imperative code.

Consider the following definition:

var intList = Enumerable.Range(0, 1000000);

If we want to refine the list down to only the even numbers we can do so with a traditional syntax such as:

var evenNumbers = new List<int>();

foreach (int i in intList)

{

if (i % 2 == 0)

{

evenNumbers.Add(i);

}

}

…or we can use a simple LINQ statement:

var evenNumbers = (from i in intList

where i % 2 == 0

select i).ToList();

I ran these tests on my laptop 100 times each and found that on average the traditional form took 0.016 seconds whereas the LINQ form took twice as long at 0.033 seconds. In many applications this difference would be trivial but in others it could be enough to avoid LINQ.

So why is LINQ so much slower? Much of the problem boils down to delegation but it’s compounded by the way we’re forced to enumerate the collection due to deferred execution.

In the traditional approach we simply iterate over the sequence once, building the result list as we go. The LINQ form on the other hand does a lot more work. The call to Where() iterates over the original sequence and calls a delegate for each item to determine if the item should be included in the result. The query also won’t do anything until we force enumeration which we do by calling ToList() resulting in an iteration over the result set to a List<int> that matches the list we built in the traditional approach.

Not Always a Good Fit

How often do we see code blocks that include nesting levels just to make sure that only a few items in a sequence are acted upon? We can take advantage of LINQ’s expressive nature to flatten much of that code into a single statement leaving just the parts that actually act on the elements. Sometimes though we’ll see a block of code and think “hey, that would be so much easier with LINQ!” but not only might a LINQ version introduce a significant performance penalty, it may also turn out to be more complicated than the original.

One such example would be Edward Tanguay’s code sample for using a generic dictionary to total enum values. His sample code builds a dictionary that contains each enum value and the number of times each is found in a list. At first glance LINQ looks like a perfect fit – the code is essentially transforming one collection into another with some aggregation. A closer inspection reveals the ugly truth. With Edward’s permission I’ve adapted his sample code to illustrate how sometimes a traditional approach may be best.

For these examples we’ll use the following enum and list:

public enum LessonStatus

{

NotSelected,

Defined,

Prepared,

Practiced,

Recorded

}

List<LessonStatus> lessonStatuses = new List<LessonStatus>()

{

LessonStatus.Defined,

LessonStatus.Recorded,

LessonStatus.Defined,

LessonStatus.Practiced,

LessonStatus.Prepared,

LessonStatus.Defined,

LessonStatus.Practiced,

LessonStatus.Prepared,

LessonStatus.Defined,

LessonStatus.Practiced,

LessonStatus.Practiced,

LessonStatus.Prepared,

LessonStatus.Defined

};

Edward’s traditional approach defines the target dictionary, iterates over the names in the enum to populate the dictionary with default values, then iterates over the list of enum values, updating the target dictionary with the new count.

var lessonStatusTotals = new Dictionary<string, int>();

foreach (var status in Enum.GetNames(typeof(LessonStatus)))

{

lessonStatusTotals.Add(status, 0);

}

foreach (var status in lessonStatuses)

{

lessonStatusTotals[status.ToString()]++;

}

In my tests this form took an average of 0.00003 seconds over 100 invocations. So how might it look if in LINQ? It’s just a simple grouping operation, right?

var lessonStatusTotals =

(from l in lessonStatuses

group l by l into g

select new { Status = g.Key.ToString(), Count = g.Count() })

.ToDictionary(k => k.Status, v => v.Count);

Wrong. This LINQ version isn’t functionally equivalent to the original. Did you see the problem? Take another look at the output of both forms. The dictionary created by the LINQ statement doesn’t include any enum values that don’t have corresponding entries in the list. Not only does the output not match but over 100 invocations this simple grouping query took an average of 0.0001 seconds or about three times longer than the original. Let’s try again:

var summary = from l in lessonStatuses

group l by l into g

select new { Status = g.Key.ToString(), Count = g.Count() };

var lessonStatusTotals =

(from s in Enum.GetNames(typeof(LessonStatus))

join s2 in summary on s equals s2.Status into flat

from f in flat.DefaultIfEmpty(new { Status = s, Count = 0 })

select f)

.ToDictionary (k => k.Status, v => v.Count);

In this sample we take advantage of LINQ’s composable nature and perform an outer join to join the array of enum values to the results of the query from our last attempt. This form returns the correct result set but comes with an additional performance penalty. At an average of 0.00013 seconds over 100 invocations, This version took almost four times longer and is significantly more complicated than the traditional form.

What if we try a different approach? If we rephrase the task as “get the count of each enum value in the list” we can rewrite the query as:

var lessonStatusTotals =

(from s in Enum.GetValues(typeof(LessonStatus)).OfType<LessonStatus>()

select new

{

Status = s.ToString(),

Count = lessonStatuses.Count(s2 => s2 == s)

})

.ToDictionary (k => k.Status, v => v.Count);

Although this form is greatly simplified from the previous one it still took an average of 0.0001 seconds over 100 invocations. The biggest problem with this query is that it uses the Count() extension method in its projection. Count() iterates over the entire collection to build its result. In this simple example Count() will be called five times, once for each enum value. The performance penalty will be amplified by the number of values in the enum and the number of enum values in the list so larger sequences will suffer even more. Clearly this is not optimal either.

A final solution would be to use a hybrid approach. Instead of joining or using Count we can compose a query that references the original summary query as a subquery.

var summary = from l in lessonStatuses

group l by l into g

select new { Status = g.Key.ToString(), Count = g.Count() };

var lessonStatusTotals =

(from s in Enum.GetNames(typeof(LessonStatus))

let summaryMatch = summary.FirstOrDefault(s2 => s == s2.Status)

select new

{

Status = s,

Count = summaryMatch == null ? 0 : summaryMatch.Count

})

.ToDictionary (k => k.Status, v => v.Count);

At an average of 0.00006 seconds over 100 iterations this approach offers the best performance of any of the LINQ forms but it still takes nearly twice as long as the traditional approach.

Of the four possible LINQ alternatives to Edward’s original sample none of them really improve readability. Furthermore, even the best performing query still took twice as long. In this example we’re dealing with sub-microsecond differences but if we were working with larger data sets the difference could be much more significant.

Query Optimization Tips

Although LINQ generally doesn’t perform as well as traditional imperative programming there are ways to mitigate the problem. Many of the usual optimization tips also apply to LINQ but there are a handful of LINQ specific tips as well.

Any() vs Count()

How often do we need to check whether a collection contains any items? Using traditional collections we’d typically look at the Count or Length property but with IEnumerable<T> we don’t have that luxury. Instead we have the Count() extension method.

As previously discussed, Count() will iterate over the full collection to determine how many items it contains. If we don’t want to do anything beyond determine that the collection isn’t empty this is clearly overkill. Luckily LINQ also provides the Any() extension method. Instead of iterating over the entire collection Any() will only iterate until a match is found.

Consider Join Order

The order in which sequences appear in a join can have a significant impact on performance. Due to how the Join() extension method iterates over the sequences the larger sequence should be listed first.

PLINQ

Some queries may benefit from Parallel LINQ (PLINQ). PLINQ partitions the sequences into segments and executes the query against the segments in parallel across multiple processors.

Bringing it All Together

As powerful as LINQ can be at the end of the day it’s just another tool in the toolbox. It provides a declarative, composable, unified, type-safe language to query and transform data from a variety of sources. When used responsibly LINQ can solve many sequence based problems in an easy to understand manner. It can simplify code and improve the overall readability of an application. In other cases such as what we’ve seen in this article it can also do more harm than good.

With LINQ we sacrifice performance for elegance. Whether the trade-off is worth while is a balancing act based on the needs of the system under development. In software where performance is of utmost importance LINQ probably isn’t a good fit. In other applications where a few extra microseconds won’t be noticed, LINQ is worth considering.

When it comes to using LINQ consider these questions:

- Will using LINQ make the code more readable?

- Am I willing to accept the performance difference?

If the answer to either of these questions is “no” then LINQ is probably not a good fit for your application. In my applications I find that LINQ generally does improve readability and that the performance implications aren’t significant enough to justify sacrificing readability but your mileage may vary.

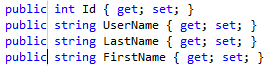

To insert the virtual modifier we just need to type (or paste) “virtual.” Here you can see that each property is now virtual and the zero-length box has moved to the end of the inserted text. What if we decide later though that these properties shouldn’t be virtual after all?

To insert the virtual modifier we just need to type (or paste) “virtual.” Here you can see that each property is now virtual and the zero-length box has moved to the end of the inserted text. What if we decide later though that these properties shouldn’t be virtual after all? We can use box selections to remove the virtual modifier from each property just as easily. In the example to the left we see a box selection highlighting the virtual modifier on each line.

We can use box selections to remove the virtual modifier from each property just as easily. In the example to the left we see a box selection highlighting the virtual modifier on each line.  To remove the text we can simply delete it. This will leave us with a zero-length box where the virtual modifiers used to be. We can then simply click or arrow away to clear the box selection.

To remove the text we can simply delete it. This will leave us with a zero-length box where the virtual modifiers used to be. We can then simply click or arrow away to clear the box selection.